|

As any parent will know, the period between about 12 and 18 years of age is where kids start to become more emotional, more sassy, more aware of wanting to fit in with their peers, more independent and generally more of a challenge to live with as their hormones start to rage.

Characteristics that we commonly see in children of this age include: novelty seeking, being easily bored, pushing the boundaries and testing the limits, as well as a need for more sleep as brains and bodies grow quickly! Social engagement with their friends is paramount, and we also see emotional intensity which includes moodiness as well as exuberance and vitality. Teens can have highly creative minds, out of the box thinking, and unique ways of looking at the world and problems, which is a positive thing when we are wanting to include them in decisions about consequences for their mis-behaviours! We, of course, want our teens to start learning to use adult logic, but for their longer-term development we also want them to start using their emotions intelligently. As our teenage children pull away from us and start to individuate, we need to stay connected to them. They stop looking at parents as the managers of their life and see them as more of a consultant they can bounce ideas off. If we don’t get it right, however, they will fire us from the job. Ideas for learning to parent effectively with your teenager include:

The steps of emotion coaching our teens are:

Being a teenager is a tough time in human development, but with a shift in our parenting techniques we can launch emotionally intelligent young people into their adult lives and keep a close relationship with each other after our baby has left home.

0 Comments

With divorce being so common these days, many divorces will inevitably involve children. Parents are often preoccupied with their own problems during the divorce process, but need to remember that whatever their differences, the needs of the children are paramount.

Divorce is going to be stressful for the children, and unless the lead up has been characterized by high levels of anger and conflict, the children will most likely prefer that the family stays intact. There can be self-blame as children can misinterpret divorce as something they are partly responsible for, and in general can feel confused and anxious about the threat to their secure foundations. The transition through divorce can involve strained relationships, reduced contact with one parent, moving home, financial hardship and high levels of conflict. Any of these reasons can lead to increased stress in a child. The length and difficulty of the transition period is entirely up to the parents. The better they can manage the stress and conflict levels, the better the adjustment for the kids. Most children are resilient enough to make the adjustment without developing emotional or behavioural problems, but there are things the parents can do ease the adjustment to the divorce and new family structure:

Dr Jules If the subject matter in this article resonates with you, then counselling might be a good option to help you to move forward. I offer a free 20-minute consultation so we can explore how I might be able to help you. This week I feature a reader question from a young person who moved to France with his mother:

Dear Dr Jules My mum is a single parent and I am 15. I was happy with my life and school in the UK, but Mum wanted to move to France, always. We moved a couple of months ago. I have no friends and she doesn't. I hate the school cos my French is not great and I was getting ready for exams. My life is a mess and she is not happy. Already money is hard for her. I know we can't afford to move back as we have no-one there. But now I am starting to resent her. Hi there Thank you for reaching out to ask for help. You are understandably frustrated with your situation, and possibly feeling somewhat out of control, which is never a comfortable place to be. Moving to a new country is a huge step for anyone, as you leave behind everything that is familiar and encounter a new language and culture. Facing all the challenges of a big move is tough enough for anyone, but particularly when you are 15, and there are some good reasons for that. When we are in the adolescent stage of life we have some vital developmental tasks to accomplish. Primarily this centers around forming strong friendships with our peers who are becoming more important in our life, while at the same time we start to pull away from our family as we need to become more emotionally and psychologically independent from them. And while all of that is going on, we know we should be focusing on school and figuring out who we are and what we want to be in life. It is an incredibly confusing and demanding time and unsurprisingly, therefore, few of us remember our teens as an easy period. In your case, you have some complicating factors added in. You don’t yet have any close friends in France, and your mum is also isolated, so you are both forced to depend on each other more than you might want to. You are also having to navigate a new school system in a language you don’t yet fully understand, and at a time in your education where the pressure is starting to build. No wonder you are feeling resentful, and that your mum is in the firing line for all your pent-up feelings. Whether you both stay in France longer term is something to be decided, but in the meantime, there are some things you can focus on to help you feel more in control:

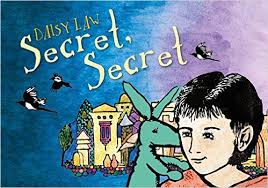

Dr Jules If the subject matter in this article resonates with you, then counselling might be a good option to help you to move forward. I offer a free 20-minute consultation so we can explore how I might be able to help you. Please contact me for more information. Following on from my last post on the book Secret Secret and helping children to disclose, this week the book’s author Daisy Law offers a detailed look at what to do when a child is ready to disclose abuse.

Daisy Law: Revealing abuse is a huge step for a child. Their future emotional health is tied to how they are allowed to express the complex range of feelings which the abuse and the abuser have caused them to feel. So the way you react to a child's disclosure of abuse can have a profound effect on how they feel about themselves and their experiences. Children pick up on reactions and may close down if they think you're reacting negatively. When a child discloses abuse, take the S.A.F.E. REPORT approach: S Support and reassure A Actively listen and be calm F Fact gathering - go slowly E Explain the next steps REPORT and note down the disclosure immediately. Survivors of abuse can go on to lead happy, healthy, productive lives just like anybody else. The key is accessing the right kind of help. Following disclosure, many people can feel further abused by individuals or systems treating them inappropriately or insensitively, so letting a disclosing child know that it is safe to report it to you is the first step. A 'SAFE REPORT' should lead to the right kinds of changes taking place for the child: intervention and healing. S Support and reassure Your face and your body language are important as the disclosing child will take cues from you. A smile and a soft tone of voice may make all the difference to a child taking the massive step of disclosing abuse to you. Remember that they will probably see disclosure as a huge risk. Not only have they been living with the abuser's wrongs, but also - as a result - had their expectations of adults skewed so they won't know what level of support and safety they can expect from you. They may also have very real fears related to threats from the abuser about what will happen if they tell anyone about the abuse. There are supportive and reassuring things which you can tell a child who has just disclosed abuse:

A Actively listen and be calm You may feel shocked and horrified to hear the abuse being disclosed, but it is vital to remember to be calm. The child disclosing abuse may feel ashamed, angry, scared and powerless. They may be especially frightened that you won't believe them, or that you may 'side' with the abuser for some reason. Particularly if the abuser is someone you know personally, you may feel outrage, anger, frustration, sadness, disbelief, disgust, shock, guilt or self-blame. But you must remain calm and in control of your emotions in order to help the child. Strained facial expressions, physical recoiling or a voice filled with any of the above emotions could be misinterpreted by the child. They need acceptance, so provide it - your emotional needs can be met later. There are reasons that the child needs you to be calm:

You can tell the child that this is a situation which was unfair and wrong, but that there are kind people out there who can help them work through it and be happy. F Fact gathering - go slowly It is normal to feel inadequate or unsure about what to do or say when a child or youth tells you about their abuse. It's natural to ask questions, especially as many children will use different words for body parts and actions. But remember that you're not an investigator. Professionals can ask for more details at a later stage, so it's vital that you don't push for more information than the child is willing to reveal now.

The child's immediate safety is an important fact to ascertain. E Explain next steps Don't make promises to the child about what may or may not happen next. The child - quite understandably - may have thoughts about revenge and/or justice being meted out to their abuser. Gently explain that what has been done to the child is wrong, and that there are people that you must tell so that they can help. But do not promise what form the intervention will take. Explain to the child that you will write down what they've said and contact experts to help:

REPORT Report and note down the disclosure immediately As soon as possible, make a written record of what the child has said. Note down their exact own words as well as you can, along with any other key details such as anything they acted out or showed you, or how their demeanour was. There may be other supporting information which you may wish to add later, but it is vital to note down what has been said while it's fresh in your mind. Keep this initial record, even if you type it up later. Along with any other drawings, writing or related material from the child themself, this may be important to investigators. Report the abuse as quickly as is possible to the police, social services, the child's doctor. There may be physical evidence which needs to be documented. Depending on the circumstances, there may also be immediate steps which authorities have to take to ensure the child's safety while investigations are made. Healing and moving forward There is nothing easy about dealing with a child's disclosures of abuse. There are many complex factors involved and every individual situation will have its own challenges. Displacement can be one of the most challenging kinds of fallout from abuse. A child who has been (or is being) abused can struggle with displaced anger and frustration. They feel anger towards the person who has hurt them, but this is often displaced and directed at loved ones - especially people they can trust and feel safe with. They may shout, swear and try to hit you, often with no warning. The child needs to express these feelings and 'get them out' so directing it all at you may be the only way they can do that and feel safe. Don't ever hit back or shout - this just reinforces a negative self view for the child. Caring, understanding and kindness are the only way. It's not their fault and it will pass. Counselling can massively increase the speed and success of healing, but every child will have different needs. Healthy activities to normalise the daily routine can be helpful. Time outside running, cycling or on other sporting activities will promote confidence and autonomy as well as focus energy away from rethinking the abuse. Sometimes getting a pet can help as a child gives the animal care. Psychological healing or 'mending the victim of abuse from the inside' can take many forms. Play therapy, biofeedback and self-soothing techniques have all had documented success in healing abused children and adults. Try whatever is available and find what works best. Children can be overcome by feelings of loneliness or unloved after abuse, so offering unconditional, non-judgmental affection is essential. Physical acceptance and plenty of gentle hugs (as and if wanted by the child) can help to avoid a child feeling 'dirty' or unworthy of affection. Let the child decide when and if to talk about their feelings, but reinforce their feelings whenever they do so. Kids need to have a clear message that they don't have to protect you from their feelings - however 'messy' their expressions of inner turmoil may be. You can get your support elsewhere and its vital that the child doesn't feel responsible for your upset on top of the abuse they've endured. Above all, be consistent and dependable. Justice is often uppermost in the minds of an abused child. Whatever the negative connotations of legal action and fears of stigma may be for an adult, avoiding punishment for the perpetrator can leave the child feeling that what was done to them - or they themselves - didn't matter. Children can be deeply worried about how many other people the abuser may hurt, so it is important not to dismiss an abused child's wishes for correct punitive measures to be taken, but to get the right professional to help them talk through all the options and consequences for everyone involved. Take the lead from a child brave enough to shout and yell. When we speak out, we can change things. Dr Jules If you have been affected by any of the issues explored in these posts, counselling could be a solution to help you to move forward. I offer a free 20-minute consultation so we can explore how I might be able to help you. To find out more, please contact me via phone or using the contact form on this site.  This week I am featuring a guest article, written for us by Daisy Law, who wrote the powerful and important book Secret Secret, an invaluable resource for anyone involved with children. As my posts generally focus on adult mental health, I thought it was about time I feature some information on ways we can take care of children’s mental health too, not least because many of the problems I see stem from childhood experiences. Daisy Law: “Children can have a lot of conflicting emotions about secrecy of any kind, and being forced to keep secrets which upset them can be part of wider safeguarding issues. Yet even the most caring family members or professionals can sometimes miss signs that a child’s wellbeing is compromised, so an engaging book which speaks directly to kids themselves would fill a very specific social need. Writing Secret, Secret was one way of addressing that need. As a former teacher, I watched growing numbers of abuse headlines from the theoretical standpoint of having completed safeguarding training and – sadly – from the practical standpoint of having taught children who were victimised by abusive adults. Within my professional life I had also had both verbal and written disclosures made to me by pupils. It seemed essential to me to give young children the message that it was OK to tell secrets, and to help them think about the different kinds of secrets which might form part of their experience. Not in a kind of grey, dour way which might rob kids of their innocence or terrify them, but in a way that prompted discussion and involvement by the children themselves. For teachers tasked with delivering safeguarding concepts to pre-schoolers or the youngest classes this filled a toolkit niche, and for some children it could be the difference between enduring or disclosing abuse. The text for Secret, Secret is carefully crafted to use emotive language which children could relate to how they feel about different types of secrets. So the most challenging phrase focuses on a “makes your insides scared and stone-cold” kind of secret without defining what that might be for any given child. The illustration depicts a child huddled in self-protective mode with a toy for comfort, but individual kids would interpret both words and images according to their own world view. I also sought to create an almost real world; similar to but not quite this one, so that children could enjoy a safe level of remove. The toys – or Dust Bunnies – Lilac and Little Blue were vital for this. Kids know how to talk to a toy, and there’s often a freedom in telling your darkest secrets to an imaginary friend. The threat of the faceless pirate can be a game, or it can represent how menacing adults can be to a child living in fear. Along with a bit of light relief fart humour with a whoopee cushion, this means that children can interpret and rationalise both the text and illustrations to fit their own life. So bottoms, beds, closed doors, fear, guilt, shame, and threat all feature subtly and can communicate to the subconscious, but happiness, joy, adventure, wonder, achievement and pride are there too. Parents who may be less confident discussing the potentially tricky area of disclosure can also help their children think about whether to ‘keep or tell’ secrets. This makes Secret, Secret a lovely bedtime read – especially as kids like to join in with the rhymes. Having a rhyming mantra which even really young pre-readers could remember was a key part of my planning for the book. Yes there are observable ‘markers’ for abuse which concerned adults may note: changes in personal hygiene; aversion to eye contact; introspection or aggression and ‘acting out’ of frustration; extremes of flinching from contact or having no discernible boundaries regarding nudity and touch, etc. But the only hard and fast rule for child safeguarding is that abusers will go to great lengths to groom for, minimise, deny and hide their abuses. Kids could be targeted at any time in even the most seemingly innocuous circumstances, so messages about their rights to privacy, boundaries and a voice need to be repeated and learned if possible. The very youngest children are the most vulnerable – without school regimes and wider societal ‘norms’ to compare their life to. So I wrote a sing-song rhyme which could fit in with a library story fun-time session or book exploration within a day nursery just as easily as it slots into the primary curriculum. At the back of the book, I’ve written some notes on the kinds of mental health or emotional issues which the general area of secrecy can give rise to for kids. There is also some advice on what to do if a child discloses more specific issues of abuse, neglect or criminality. Secret, Secret is already being used effectively by specialist child protection Police officers, social workers, charity workers and psychologists. Teachers are incorporating some of the cross-curriculum links within general lessons and also using the book for circle time discussions and subtle safeguarding, as well as leading group reading and literacy work from the rhyming text. Whether you read the book with a child as part of therapy, prevention work or as a parent keen to open up even the trickiest subjects, Secret, Secret invites children to speak up and give their opinions. The book ends with non-leading questions, so it’s important to maintain that sense of openness for whatever discussions ensue. Children take many cues from how adults react, so whether a child makes a disclosure of inappropriate behaviour or simply wants to talk about which things it’s OK to keep private, we have to bear each developing individual in mind. Support and encouragement – verbally and from stance or facial expressions – can let a child know that they’re safe to talk with you about any subject and that can be the most important step in freeing someone from the burden of a difficult secret which they carry”. Dr Jules In my next post I will feature some advice from Daisy Law on what to do when a child discloses abuse. If you are affected by the issues raised in these articles, counselling can help you to move forward. I offer a free 20-minute consultation so we can explore how I might be able to help you. This article was originally published at: www.englishinformerinfrance.com/full-article/Secret-Secret-Helping-Children-to-Disclose |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|